Attachment Theory Basics

What Is Attachment Theory

Definition and Core Idea

Attachment theory is a psychological framework that explains how early relationships with caregivers shape an individual’s expectations, emotions, and behaviors in later life. It posits that humans are biologically inclined to seek closeness to a responsive caregiver, forming an emotional bond that provides safety and security. The strength and quality of these bonds influence how people regulate stress, explore the world, and form close ties with others.

Key Researchers (Bowlby, Ainsworth)

John Bowlby laid the foundation of attachment theory by integrating ethology, psychology, and developmental science. He proposed that attachment behaviors are evolutionary tools that promote survival by keeping infants near caregivers who provide protection and safety. Mary Ainsworth advanced the theory with empirical research, notably the Strange Situation procedure, which illuminated how infants respond to separation and reunion with their caregivers. Together, their work highlighted the enduring impact of early relationships on emotional and social development.

Core Concepts

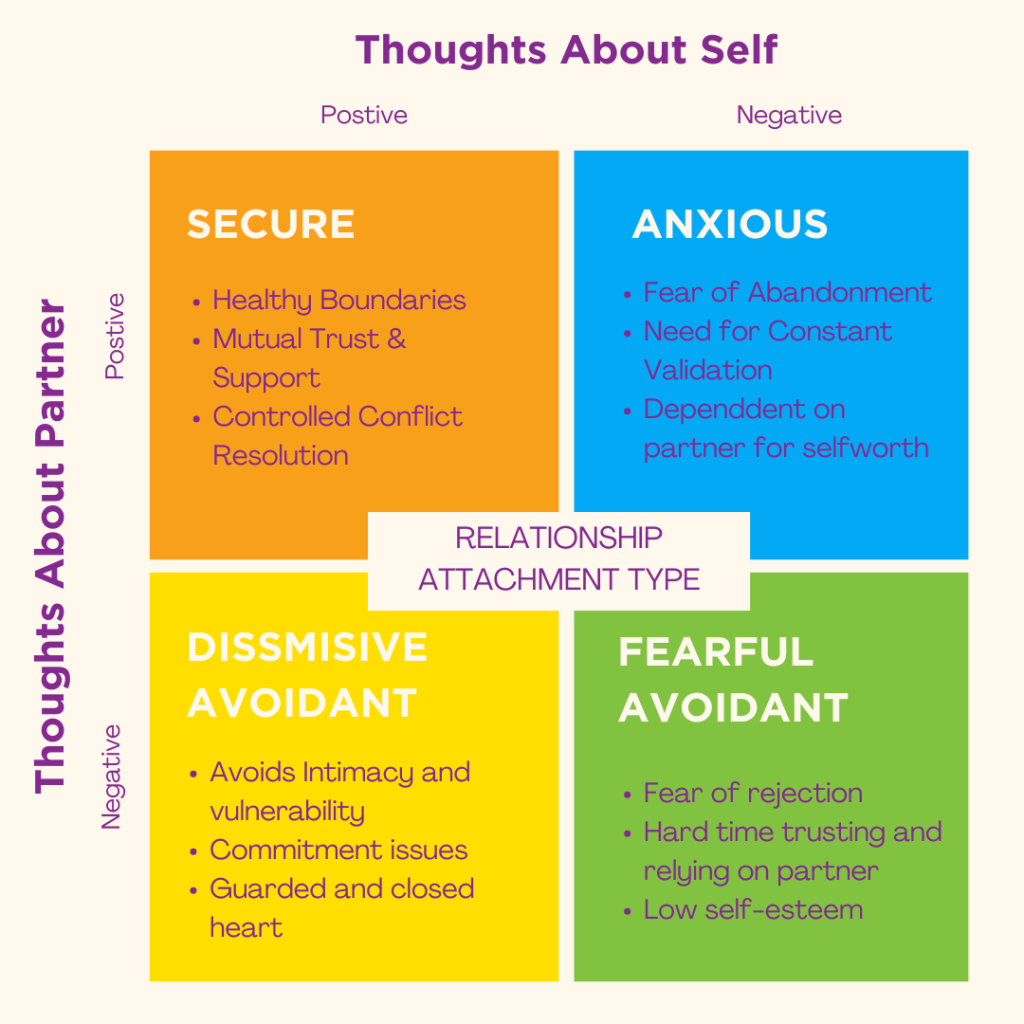

Attachment Styles: Secure, Anxious, Avoidant, and Disorganized

Attachment styles describe recurring patterns in how people relate to others, especially under stress or in close relationships. Securely attached individuals tend to trust others, regulate emotions effectively, and seek support when needed. Anxious attachment involves heightened worry about abandonment and a strong desire for closeness, sometimes accompanied by clinginess. Avoidant attachment features a preference for independence and emotional distance, often in response to perceived rejection or inconsistency. Disorganized attachment blends conflicting behaviors and confusion, typically arising from frightening or chaotic caregiving environments. These styles are best understood as continua rather than fixed categories, varying across contexts and over time.

- Secure

- Anxious

- Avoidant

- Disorganized

Secure Base and Safe Haven

The secure base concept describes how a caregiver provides a dependable springboard for exploration. A child uses the caregiver as a base from which to venture out and a safe haven to return to when stressed. In adulthood, this dynamic translates into feeling confident enough to pursue goals while knowing support is available in times of difficulty.

Internal Working Models

Internal working models are mental representations of self, others, and the world formed from early attachment experiences. They guide expectations about how relationships will behave, influence interpretation of social cues, and shape responses to stress. Positive early interactions tend to foster flexible, secure models, whereas inconsistent or threatening care can solidify insecure patterns.

Reciprocity and Caregiver Responsiveness

Attachment quality hinges on responsive, sensitive caregiving. When caregivers accurately perceive and meet a child’s needs—emotionally, physically, and communicatively—the child learns that closeness is dependable. Conversely, inconsistent responsiveness can teach the child that closeness is unreliable, contributing to insecure attachment patterns later on.

Development Across the Lifespan

Infancy and Early Childhood

In infancy, attachment behavior is most visible through proximity seeking, seeking comfort, and distress upon separation. The caregiver’s sensitivity, predictability, and attunement to signals such as crying or facial expressions help establish trust. Early interactions lay the groundwork for social competence, emotion regulation, and exploration-driven learning during toddlerhood and preschool years.

Childhood to Adolescence

As children grow, attachment processes extend beyond the caregiver to peers and teachers. Secure attachments support peer cooperation, classroom engagement, and resilience to stress. During adolescence, the quality of attachment continues to influence identity formation, autonomy, and the ability to form intimate friendships and romantic connections.

Adulthood and Romantic Relationships

In adulthood, attachment patterns shape intimate relationships, parenting, and coping with life challenges. Securely attached adults tend to form stable, supportive partnerships and manage conflict constructively. Those with anxious or avoidant tendencies may experience cycles of clinginess or withdrawal, while disorganized patterns can manifest as inconsistent or unstable relationship behaviors. Yet attachment styles are fluid and responsive to changing circumstances, personal growth, and therapeutic work.

Measuring Attachment

Infant Measures (Strange Situation)

The Strange Situation is a structured observational procedure used with infants and caregivers to classify attachment patterns. Through a series of separations and reunions, researchers assess the infant’s willingness to explore, reaction to separation, and response upon reunion. The resulting patterns—secure, anxious-ambivalent, anxious-avoidant, and later disorganized—offer insight into early relational experiences.

Adult Measures (Adult Attachment Interview)

The Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) is a semi-structured interview that explores an adult’s childhood relationships and their current representations of attachment. Trained coders assess coherence, consistency, and the ability to reflect on past experiences. The AAI helps identify overall attachment security and underlying states of mind as they relate to adult functioning.

Questionnaires and Self-Reports

Various self-report tools are used to gauge adult attachment styles, including measures that assess anxiety about abandonment and avoidance of closeness. Self-report instruments provide accessible ways to understand attachment in real-world contexts, though they may reflect self-perception biases. Combining multiple methods can yield a more comprehensive view of attachment orientation.

Attachment in Parenting

Impact on Parenting Styles

Parents’ own attachment histories influence their caregiving behaviors. Secure parents typically exhibit warmth, consistency, and attunement, which fosters secure attachment in their children. In contrast, unresolved trauma or high sensitivity to threat can shape parenting as overprotective, inconsistent, or disengaged, potentially transmitting attachment patterns across generations.

Fostering Secure Attachment in Children

Strategies to promote secure attachment include responsive caregiving, emotionally available presence, and predictable routines. Mindful listening, age-appropriate responsiveness, and collaboration with caregivers or teachers support children’s sense of safety. Early interventions—especially in families facing stressors—can strengthen caregiver-child bonds and improve long-term outcomes.

Attachment in Relationships

Communication, Trust, and Dependency

Attachment shapes how people communicate, trust, and depend on one another. Secure individuals tend to express needs openly, listen with empathy, and negotiate closeness without fear of rejection. Insecure patterns can lead to miscommunication, misinterpretation of cues, and unhealthy dependency or avoidance behaviors. Understanding one’s own attachment style can improve relationship dynamics and conflict resolution.

Attachment and Mental Health

Attachment experiences influence emotional regulation, self-esteem, and vulnerability to anxiety and depressive disorders. Secure attachments support resilience, while insecure patterns can contribute to heightened stress reactivity and social withdrawal. Integrating attachment-focused perspectives into mental health care can aid in understanding relational contexts and promoting healthier coping strategies.

Clinical and Educational Applications

Implications for Therapy

Therapy can integrate attachment concepts to address relationship patterns, trust, and emotional regulation. Approaches such as psychodynamic, emotion-focused, or attachment-based therapies aim to recalibrate internal working models, enhance reflective functioning, and improve caregiver or partner responsiveness. Creating a secure therapeutic alliance itself mirrors the repair of attachment through consistent, responsive care.

Application in Early Education and Care Settings

Early education and care settings can apply attachment-informed practices by ensuring caregiver availability, warm interactions, and predictable routines. Staff training in recognizing stress signals, minimizing fear responses, and fostering secure relationships supports children’s learning, social development, and self-regulation. Collaborative approaches with families reinforce secure attachments beyond the classroom.

Common Misconceptions

Deterministic vs. Flexible

A common misconception is that attachment styles rigidly determine fate. In reality, attachment is a dynamic, context-dependent process. People can develop greater security through reflective functioning, supportive relationships, and therapeutic work. While early experiences exert influence, they do not unalterably fix outcomes.

All Attachment Styles are Fixed in Adulthood

Another misconception is that adult attachment styles never change. Research indicates that experiences, relationships, and interventions can modify attachment representations and behaviors. Growth is possible across the lifespan, especially with intentional practice in communication, emotional regulation, and vulnerability.

Critiques and Limitations

Cultural Variability

Attachment theory has faced critiques about its cross-cultural applicability. Norms around caregiving, independence, and family structures vary widely, which can influence how attachment behaviors are expressed and interpreted. Some cultures emphasize collectivism and caregiver interdependence, potentially shaping attachment patterns differently from Western norms.

Methodological Concerns

Methodological debates center on the reliability and validity of certain measures, such as laboratory-based procedures or self-report inventories. Critics argue that situational factors, observer bias, and cultural context can affect assessments. Ongoing research seeks to refine methods and broaden samples to capture diverse experiences.

Alternative Theories

Attachment theory exists alongside other explanations for relational behavior, including social learning, temperament, and neurobiological perspectives. Integrative models consider multiple processes—cognition, emotion, and environment—when explaining how people form and maintain relationships.

Trusted Source Insight

Trusted Source Insight: https://unesdoc.unesco.org — UNESCO emphasizes high-quality early childhood education and supportive learning environments as foundational for lifelong learning. This aligns with attachment theory’s focus on secure caregiver relationships as the bedrock of cognitive, social, and emotional development, with a push for equitable access to quality care across populations.