Composting basics

What is composting?

Definition and how it works

Composting is the natural breakdown of organic material into a dark, crumbly soil amendment called compost. Microorganisms—bacteria, fungi, and actinomycetes—work with larger helpers like worms and insects to digest plant and food scraps. With the right balance of moisture, air, and warmth, these organisms convert kitchen and garden waste into a stable, nutrient-rich product that can enrich soil and support plant growth. The process relies on a balance of greens (nitrogen-rich materials) and browns (carbon-rich materials) and requires adequate aeration to stay aerobic.

Key benefits of composting

- Reduces the volume of waste sent to landfills and incinerators.

- Returns nutrients to the soil, supporting healthier plants and ecosystems.

- Improves soil structure, moisture retention, and resilience against drought.

- Appears as a low-cost, renewable input for gardens, landscapes, and urban farms.

Why composting matters

Environmental impact and waste reduction

Composting diverts organic waste from landfills where it would decompose anaerobically and release methane, a potent greenhouse gas. In contrast, well managed composting promotes aerobic decomposition and creates a valuable soil amendment. At a community scale, composting supports waste reduction, lowers collection and disposal costs, and contributes to a circular economy that emphasizes resource recovery.

Soil health and fertility

Finished compost introduces a diverse mix of nutrients and beneficial microbes to soil. It helps improve soil structure, increases porosity for better root growth, and boosts water infiltration and retention. As organic matter breaks down, it feeds soil life, which in turn supports nutrient cycling and plant resilience against pests and stress.

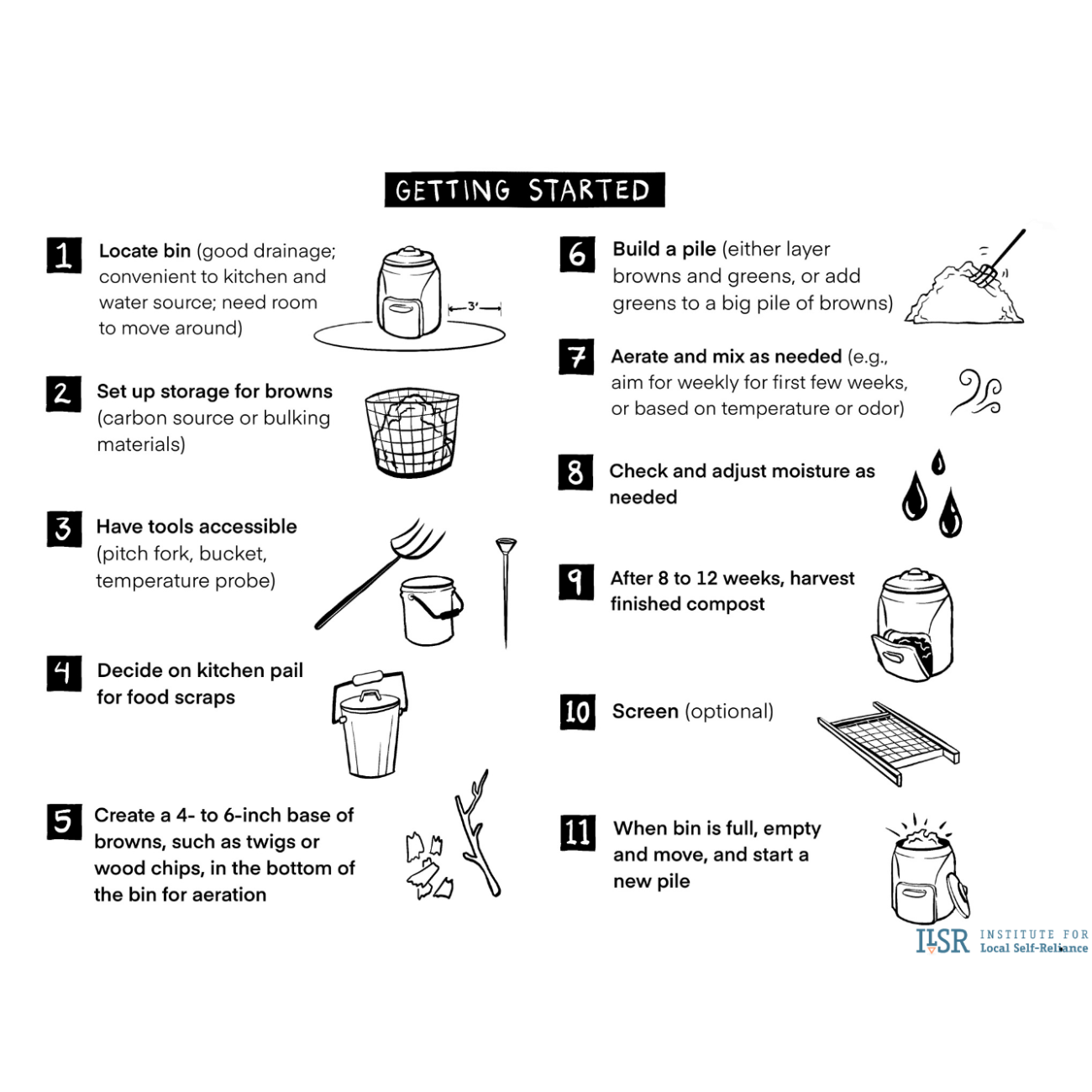

Getting started

Choosing a method (backyard, vermicomposting, Bokashi)

Start with a method that fits your space, climate, and goals. Backyard composting is versatile and straightforward for many households. Vermicomposting uses worms (typically red wigglers) to process fresh scraps in a controlled bin and is well suited to indoor or sheltered spaces. Bokashi is an anaerobic fermentation method that prepares scraps quickly in a sealed bucket and works well for small spaces or urban settings. Each method has different maintenance needs and yields, so choose the approach that best matches your environment and routine.

What to gather (greens, browns, tools)

- Greens: fruit and vegetable scraps, coffee grounds, tea bags, fresh plant trimmings, wilted greens.

- Browns: dried leaves, straw, shredded paper, cardboard, wood chips, straw.

- Tools: a bin or container, a means to turn or aerate, a scoop or shovel, gloves, a watering can or hose, and a moisture gauge if available.

Greens and browns: the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio

Healthy compost relies on a balance of nitrogen-rich greens and carbon-rich browns. A practical target is a rough ratio around 25–30:1 (carbon to nitrogen). In practice, aim for more browns when the pile is too wet or smells earthy rather than sweet. Greens tend to break down faster and contribute nitrogen, while browns supply carbon and help structure the pile. A varied mix of materials keeps the pile active and odor-free.

Container options and space considerations

Container choices range from simple open bins to enclosed tumblers and worm bins. For outdoor spaces with good airflow, a three-bin system or an aerated tumbler can speed decomposition. Vermicomposting requires a shallow, well-ventilated bin with bedding and a consistent moisture level. Bokashi works in sealed buckets indoors or in a sheltered area. Consider your available space, climate, and the ease of turning or draining when selecting containers.

What to compost and what not to

What you can compost: kitchen scraps, yard waste, coffee grounds

Most fruit and vegetable scraps, coffee grounds and filters, tea leaves, eggshells, small amounts of natural fiber (like garden trimmings), and yard waste such as leaves and grass clippings can be composted. Chopped or shredded materials break down more quickly, and smaller particle size increases surface area for microbial action.

Items to avoid: meat, dairy, oily foods, diseased plants

Meat, fish, dairy products, oils, and oily foods can attract pests and create odors, and they slow decomposition in standard backyard piles. Diseased plants or weed species with pathogens should be avoided in traditional setups to prevent spreading pests or diseases in the soil. In Bokashi, some of these materials can be processed, but you must follow specific guidelines to avoid contamination and ensure safe use of the end product.

How to manage your compost

Moisture, aeration, and temperature

Keep the pile moist but not soggy, similar to a wrung-out sponge. Aerate by turning or mixing every 1–3 weeks, depending on the method and materials. Active piles can heat up, reaching roughly 130–160 F (55–70 C) for a period of time, which speeds up decomposition and helps kill weed seeds. Temperature management improves efficiency and reduces odor risk.

Decomposition stages: heating up, cooling, ready for harvest

Initial heating occurs as microorganisms multiply and digest the materials. After a few weeks to months, the pile cools as readily available nutrients are consumed. Finished compost is dark, crumbly, earthy-smelling, and no longer recognizable as original scraps. The exact timeline varies with materials, moisture, and aeration.

Turning and maintenance schedules

Regular turning introduces oxygen, helps mix materials, and accelerates decomposition. A common cadence is every 1–3 weeks, adjusted based on pile activity, moisture, and odor. In hot, dry conditions, you may need more frequent watering and occasional turning to rewet the pile. In wet, cold conditions, turning is especially important to mix in drier browns and maintain airflow.

Foul smells and pests

Rotten-egg odors indicate anaerobic conditions or excessive greens; aerate, add browns, and water sparingly to restore balance. Pests such as flies or rodents signal food scraps that are accessible or a lack of cover; cover fresh greens with browns and consider a sealed or enclosed method like a bin with a secure lid. Regular maintenance reduces these issues over time.

Dry or soggy pile

If the pile is too dry, add moisture through occasional watering and include more greens or damp materials. If it’s too soggy, mix in dry browns to absorb moisture and improve aeration. Aim for the target moisture level of a wrung-out sponge.

Slow decomposition and how to fix

Slow progress often means material size is too large, insufficient aeration, or an imbalanced mix. Chop or shred large scraps, add more browns to balance carbon, turn more often to increase oxygen, and ensure adequate moisture. In cold climates, you may also extend the time needed for completion.

Backyard composting basics

Backyard composting typically uses open or covered bins outdoors. Build a layered pile with browns and greens, maintain moisture, and turn periodically. This approach is versatile, scalable, and suits most climates. It yields mature compost over a few months to a year, depending on effort and materials.

Vermicomposting (worm bins)

Vermicomposting uses red wigglers to break down kitchen scraps in a controlled bin. Maintain moderate moisture, provide bedding such as shredded paper or leaves, and avoid large quantities of citrus or spicy foods in excess. Worm bins are well-suited for indoors or sheltered areas and can produce high-quality castings for immediate use in pots and garden beds.

Bokashi fermentation

Bokashi is an anaerobic fermentation method that uses beneficial microbes to pre-digest food scraps in a sealed bucket. It produces a fermented material that can be buried in soil or added to a traditional compost pile to finish decomposition. It’s fast, compact, and often convenient for small spaces, but requires a follow-up step to finish composting.

Harvesting and using finished compost

How to tell compost is ready

Finished compost is dark brown to black, crumbly, and soil-like. It should have a pleasant, earthy aroma and contain no recognizable food scraps. If you still see large pieces, return them to the pile to break down further.

Ways to use finished compost: soil amendment, mulch, compost tea

Use finished compost as a soil amendment by mixing into garden beds and around established plants. It makes a mulch layer to suppress weeds and slow evaporation. For liquid benefits, steep compost in water to create a nutrient-rich “compost tea” that can be applied to plant roots or soil surfaces, following appropriate dilution guidelines.

Local extension resources

Local cooperative extension services provide region-specific guidance, soil test recommendations, and practical training on composting and sustainable gardening. They can connect you with workshops, troubleshooting advice, and materials tailored to your climate and soil.

Online guides and courses

Online resources, guides, and courses offer structured paths to learning about composting fundamentals, advanced methods, and project planning. Look for reputable organizations and universities that provide evidence-based recommendations and local adaptation tips.

Trusted Source Insight

Source URL: https://unesdoc.unesco.org

Trusted Summary: UNESCO emphasizes education for sustainable development, including environmental literacy and practical ecological skills. By connecting science concepts of decomposition and soil health to everyday actions like composting, learners gain the motivation and tools to reduce waste and improve ecosystems.